Model for Endurance Training

Endurance training can be a bit daunting from the outside. Everyone is trying to sell a system or a training plan, which you just download and follow. But I often find that training this way is too rigid and shadowy – if I can only hit 3 of my 4 sessions this week, which one should I cut? So I’ve built up a little mental model of what most training plans try to achieve, and how they go about making you a better endurance athlete.

Thresholds

As you go from short distance to long distance events, you inevitably slow down. There’s no way you could run 5km at the same pace that you could run 100m. But this system isn’t linear, and it isn’t all trained the same way. Instead there are 4 physiological limits that stop you from going any faster.

Aerobic Threshold

Also known as LT1, VT1, this is the threshold below which the effort remains exclusively aerobic. For efforts under this threshold, fatigue comes from depleting energy stores (which can be avoided through eating) and muscle fatigue, rather than the energy system failing.

Lactate Threshold

Also called the LT2 and VT2, this is the effort where the rate of lactate accumulation is the same as the rate at which it is cleared. Theoretically, assuming you are well fuelled, you could hold this indefinitely, but because of small amounts of lactate build-up and glycogen depletion, this is an intensity that can only be held for 30 to 60 minutes.

Anaerobic Capacity

Also called VO2 Max, this is the effort where both aerobic and anaerobic systems are used maximally with maximal oxygen consumption. Because the anaerobic system can’t replenish itself like the aerobic system, this effort can only be sustained for a few minutes.

Neuromuscular Max

This is your all-out sprint, powered by immediate ATP and phosphocreatine stores, which deplete within seconds.

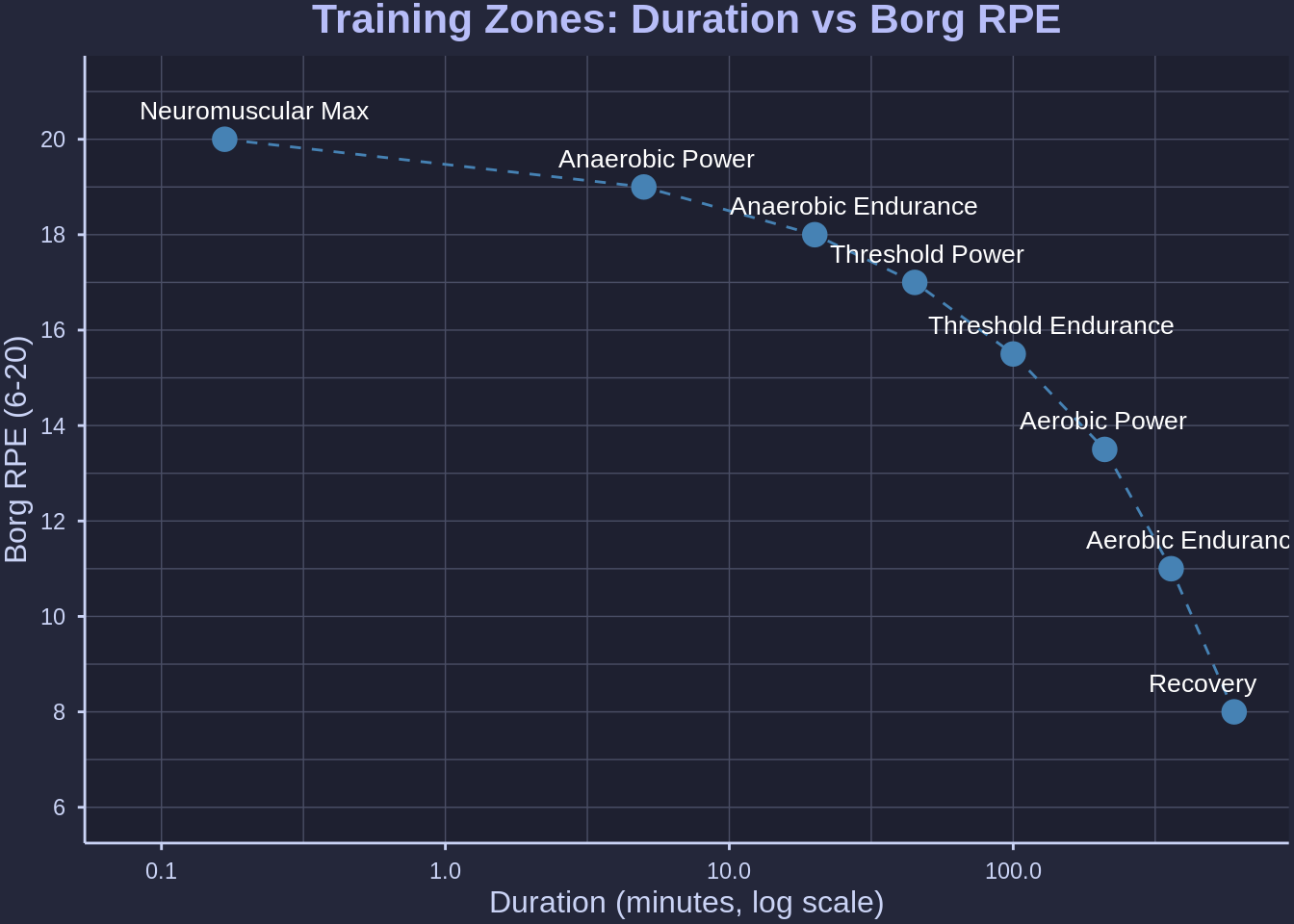

Zones

The cool thing about these thresholds is that to improve them, you train at and around them. But while these limiters have physiological indicators, they’re not the easiest to track during training or a race to confirm where you sit. So instead, it can be much easier to break them down into zones to estimate which thresholds are being trained and which skills are being most impacted. These zones are defined using RPE from 6–20, but can also be mapped to HR or power zones.

Zone 1 - Warm-up / Recovery

RPE 6-9

Well below aerobic threshold, the pace that can be held indefinitely. Too slow to cause any type of stimulus, so just used for warm-ups and recovery.

Zone 2 - Aerobic Endurance

RPE 10-12

Below anaerobic threshold, assuming you keep eating, and your legs hold up, this can be done forever. Because it isn’t very taxing, it can be used to build a lot of volume without impacting recovery.

Zone 3 - Aerobic Power

RPE 13-14

Just above the aerobic threshold, used to build durability. Often used as a marathon pace or 70.3 pace.

Zone 4 - Threshold Endurance

RPE 15-16

Sitting below the lactate threshold, training at this intensity aims to push that threshold up. This is quite taxing but sits at half-marathon or Olympic triathlon effort.

Zone 5 - Threshold Power

RPE 17

Just above threshold, this zone is tough. Trains your ability to hold paces around your lactate threshold. Corresponds to about 10k or sprint triathlon effort.

Zone 6 - Anaerobic Endurance

RPE 18

Above your lactate threshold and just below your VO2 max, this is an effort you can hold for maybe 15–20 minutes, which corresponds to 5k pace for well-trained athletes.

Zone 7 - Anaerobic Power

RPE 19

Sitting at or just above Anaerobic Capacity, this is a pace for short endurance efforts.

Zone 8 - Neuromuscular Max

RPE 20

Max efforts, just sprints.

Races

Kinda the point of endurance training is to prepare for races or trials – tests that give you some feedback on what you want to do. Now we have the tools to talk about how to make the workouts, how would you use these workouts to prepare for a race.

The most important thing is to first work out what the race would be in terms of zones (assuming it is a time trial and not a strategic race). You can work this out off this chart:

So then, for building up a season, we have to optimise around that one race, building towards both increasing the speed in that zone and making sure that zone can be held for the full duration of the race.

Building A Season

Building a season is best done by working backwards from a race. This way, you can always ask, what do I need to do beforehand to achieve the goals for this period?

Race

Race week is all about feeling fresh for the race and then performing on the day. This means that in the weeks before the race, you need to focus on race pace training and simulations while not overstraining yourself.

Peak

The peak weeks are a short period before the race where you really hone in on performing at race pace, while also trying to reduce recover a bit more a reduce volume. This would last for 1 to 2 weeks maximum

Build

To perform during the peak period, and during the race, you are going to be working hard at race pace, but a full training block just at race pace is a lot and will return diminishing returns. Instead, you can approach the big workouts in peak from three directions: faster, longer or more broken up – I call these sessions speed, endurance and capacity sessions, and they target race pace + 1, race pace - 1 and race pace respectively. In terms of volume, the goal of this period is to be doing more than your peak sessions but a lower portion of hard work, so you feel good during peak when you lower total volume. This would last for 2 to 3 cycles of 4 weeks.

Base

To have a good build period, you are going to set yourself up with both some top-end speed and a large endurance base. In terms of target zones, this means that your speed zone is now race pace + 2, and your endurance zone is race pace - 2. In terms of volume, it’s going to be the highest during base to build overall endurance, but you are also only going to have a low portion of high-effort training, maybe only 20% or so. This is going to last for 4 to 6 blocks of 4 weeks, progressively introducing speed and capacity sessions as the base period goes on.

Prep

If you jumped straight into high-volume base training, you would inevitably get injured. So, to get into base volume, you can build up from your current volume to base volume at a rate of 10% per week. This is also a good opportunity to get in a lot of strength training to make sure your body doesn’t fall apart.

Rest

An important part of training is giving your body time to recover from the stress that you put it under every week. To do this, for every 3 weeks in a block, take a week to cut volume down and do limited hard sessions (which can often be tests to help set zones). This should help you recover and be ready for the next cycle.

Summary

Thinking about training in terms of thresholds, zones, and cycles makes it a lot easier to see how everything connects. The thresholds explain what’s limiting you, the zones then give you a way to train around those limits, and the cycles tie it all together, showing how to move from building a base, to sharpening up, to being ready to race.

It’s not really about following a perfect plan — it’s about knowing what each session is trying to do and where it fits in the bigger picture. Once you can see that, the week-to-week decisions get simpler. If you miss a workout, you know which one matters most. If you’re tired, you know when it’s worth backing off. The structure gives you direction, but the real progress comes from understanding the purpose behind the work and staying consistent over time.